In January, I boldly claimed that I was in the process of starting my own Farmhouse brewery. Today, 3 Dec, that statement seems as cavalier as it did then… but for totally different reasons. There is no less truth in the claim now as there was then, but, as you will understand below, the actualisation of this dream no longer carries the same time line.

In September 2016, Chris-Topher Brewing Co Pty Ltd signed a commercial lease for an industrial space in Marrickville, NSW… Chris is my business partner and with my name being Topher, the company we formed has this silly hyphenated name… don’t worry thats not the name of our brewery. If you are a Sydneysider then you may recognise that Marrickville is in the inner city of Sydney, not at farm, in no way rural and directly in the flight path of incoming international flights.

So as a Farmhouse beer enthusiast, what I am I doing with a space in the city… not making Farmhouse beers that is for certain.

Instead in May 2017 (fingers crossed) Chris and I will open Wildflower Brewing and Blending in our beautiful 1890’s ex-metal foundry. To help me and you get our heads around this, I might try to explain below what it is that we are doing and why.

The Name

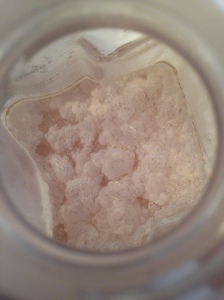

I have come to realise that Wildflower, as the name of our brewery, means primarily two things to us. Firstly the literal reading, we are focused on making 100% wild ales. All of the beers from this blendery will be fermented with a mixed culture that I have foraged, wrangled, harvested from New South Wales. All of the bugs in our beers, as it were, are entirely indigenous to this state. This was really important part to me, and I’ll explain more about the beers later. Flower, well a number of my cultures were grown off of flora. If you live in this country or have visited, you will know what I mean when I say that the native plant life is exotically beautiful. My best two captures so far actually have come from flowers, namely Wattle blossoms and dandelions. In this first way, the name evokes exactly what the beers are and where they are from.

Its second reading is slightly less tactile. This meaning surrounds the nomenclature and imagery that a word like Wildflower evokes. Soft words like subtle, nuanced and beautiful paired with visuals of colour, life and earthly things. In this instance, Wildflower conjures a less domineering, engineered psyche. This is my true goal as a blender, to bring this spirit to the beer world.

The Product

As mentioned before we are specialising in mixed ferment ales. Pre-industrialisation and the isolation of pure yeasts, brewers made their beers with a mixture of yeast strains rather than single strains. Each brewer would have their house culture (the mixture of yeasts) that they cultivated and propagated. The culture might be a mix of a a few different brewer’s yeasts in addition to naturally occurring wild yeast and souring bacteria from their environment. Over time, these cultures defined a brewery’s house character and would have made them distinguishable from another brewery down the road.

Worldwide now, there are a handful of breweries rediscovering how to make beer using a diversity of yeasts, including wild yeast rather than use a monoculture. Using mixed culture beers takes a certain amount of submissiveness to mother nature and her curious ways. Opposite to single strain pure yeast fermentations, mixed cultures are prone to behave unpredictably and take a great deal of patience from the brewer. These inconsistency and time requirements pose distinct risks for any business. It is understandable that nearly all beer is a product of quick, clean, certain pure yeast fermentations. We feel, however, that the transformation of flavour and abundant harvest of esters mixed fermentations produce underly a character absent in pure yeast beer making. Like others who share our interest, we echo the sentiment of Marc H. Van Laer, 20th Century Belgian brewing scientist, when he says:

“It is certain that the introduction of pure yeasts into industrial fermentation does not constitute the crowning achievement of a system that is henceforth immutable. It seems, for example, that if the application of the pure cultures method has improved the average quality of the beer, if it has decreased the chances of infection, it has given us beer with less character than before.”

Our brewery is only but a part of a larger movement to rediscover the flavours of natural fermentations. Artisanal bakers have revived ancient methods of bread making and are expressing local flavours in their sourdough. Each harvest, more and more winemakers around the world are allowing the native yeasts, resident on the skins of their ripe grapes, to ferment their wines adding an extra element to their terroir. There are cider makers, picklers, foragers, and a whole myriad of food enthusiasts coming back in touch with the microflora from their region. Wildflower, out little brewery/blendery in Marrickville Australia, is an attempt to explore this movement from a beer perspective.

Our Vision

Beer is the common man’s drink, to be consumed commonly. We simply want to provide a quality product made of our region for the people of our community. No time for pretentiousness or snobbery, we feel that the conversation happening around our product is always more important than the conversation about it.

If you have any questions about the brewery or its ethos, please don’t hesitate to ask me. I will be writing more pieces that deal specifically with the details of our beer… our culture, recipes, methods, etc. I have been very lucky to have been trusted with snippets of knowledge from the brewing community that help me tremendously in making these beers so it is only right for me to pass these and my own findings on. If you are inclined to social media here are links to our twitter, Facebook and instagram. At the time of writing this post, they are mostly void of content… but that won’t last long.